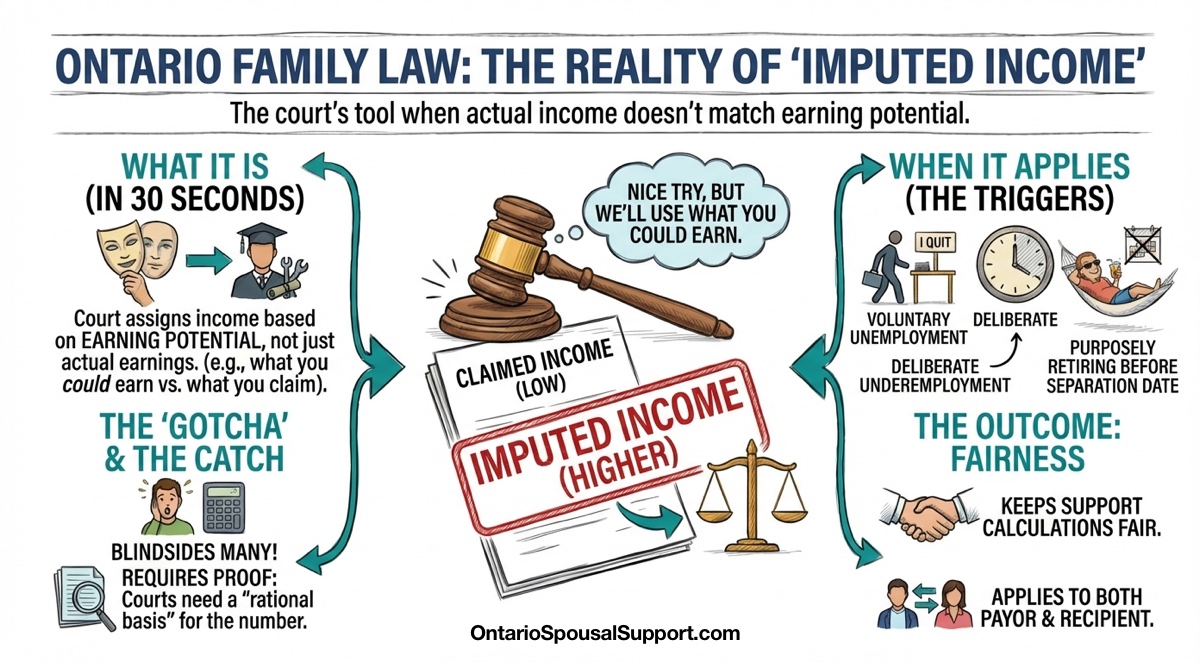

Imputed income is when the court says, "Nice try, but we're going to calculate support based on what you could earn—not what you claim to earn."

It's the legal system's answer to people who try to game the numbers. And it works both ways—it can apply to the person paying support or the person receiving it.

This is one of those gotchas that blindsides people. You run the numbers, think you know what support will be, and then your lawyer mentions imputed income and suddenly everything changes.

Imputed Income in 30 Seconds

What it is: The court assigns an income amount based on earning potential, not actual earnings

When it applies: Voluntary unemployment, deliberate underemployment, or hiding income

Who it applies to: Either spouse—payor OR recipient

The catch: Someone has to prove it, and courts need a "rational basis" for the number they pick

What Imputed Income Actually Means

Let's cut through the legal jargon. "Imputed income" just means the court assigns you an income for support calculation purposes—regardless of what your tax return says.

The word "impute" literally means "to attribute." The court is attributing income to someone based on what they should reasonably be earning, given their skills, education, work history, and the job market.

This matters because spousal support (and child support) are calculated based on income. If someone can manipulate their income—by quitting their job, going part-time, or hiding money through a business—they can manipulate the support amount.

Courts aren't naive. They've seen every trick. And imputed income is their tool to keep things fair.

When Courts Will Impute Income

Section 19 of the Federal Child Support Guidelines (which Ontario courts also apply to spousal support) lists the situations where income can be imputed. But here's what that looks like in real life:

1. Voluntary Unemployment ("They Quit to Screw Me Over")

Your ex had a perfectly good job making $90,000 a year. Then, right around separation, they quit. Now they're "between opportunities" and claiming they should only pay support based on zero income.

The court will likely impute their previous salary—or something close to it. Quitting your job to avoid support obligations is exactly what this rule was designed to catch.

Example: The Convenient Career Change

David was a sales manager making $120,000. Two months before separation, he quit to "pursue his passion" for woodworking. His new business shows a loss on paper.

What happens: The court imputes his previous income of $120,000 for support calculations. His "passion project" doesn't change his obligations.

2. Deliberate Underemployment ("They Could Work More")

This one's trickier. Your ex is working—but not at their full capacity. Maybe they have a law degree but they're working at a coffee shop. Maybe they're a skilled tradesperson working 20 hours a week when they could easily work 40.

If the underemployment is deliberate, the court can impute income based on their full earning potential.

3. The Support Recipient Who Won't Work

This is the frustration I hear most often: "Why should I pay more just because my ex refuses to get a job?"

Here's the deal: if you're receiving spousal support, you have an obligation to make reasonable efforts to become self-sufficient. That's not just a moral expectation—it's embedded in the law.

If you're capable of working, have no young children at home, and just... don't feel like it, the court can impute income to you. That means your spousal support gets calculated as if you were earning something, which reduces what you receive.

Example: The Spouse Who Won't Look

Lisa was a stay-at-home mom during the marriage. The kids are now 15 and 17. She has a college diploma and previous work experience. She's made no effort to find work in the two years since separation.

What happens: The court imputes income to Lisa based on what she could reasonably earn—maybe $45,000 in an administrative role. Her spousal support is calculated using that number, not zero.

4. Hiding Income Through a Corporation

This is where things get complicated. If your ex owns a business or has a private corporation, there are ways to make income "disappear" on paper:

- Leaving money in the corporation as retained earnings

- Paying personal expenses through the business

- Taking dividends instead of salary (or vice versa) for tax benefits

- Paying family members who don't actually work there

Courts see through this. They'll look at the corporation's total income, retained earnings, and whether the business is paying for things that should be personal expenses. Then they'll impute an income that reflects the actual economic benefit your ex is receiving.

(For more on this, see our article on Self-Employed Income and Spousal Support.)

5. Cash Businesses and Unreported Income

Some businesses deal primarily in cash. Restaurants, contractors, some retail businesses. If the reported income seems suspiciously low given the lifestyle, courts can impute a higher income.

The classic red flag: they're reporting $40,000 a year but somehow own two cars, a boat, and take vacations to Mexico every winter. Courts aren't stupid.

The Burden of Proof: Who Has to Prove What

Here's where it gets legally important. If you want income imputed to your ex, you have to prove it.

Specifically, you need to prove that their unemployment or underemployment is voluntary—that it's a choice, not a circumstance beyond their control.

Once you prove that, the burden shifts. Your ex then has to prove either:

- Their unemployment/underemployment isn't voluntary, OR

- It falls under an exception (childcare needs, health issues, education), OR

- It's reasonable in the circumstances

The good news: once you've established that income should be imputed, you don't have to prove the exact amount. The court will figure that out based on evidence of earning potential.

What Evidence Do Courts Look At?

If you're trying to get income imputed to your ex (or defending against it being imputed to you), here's what matters:

Employment History

What did they do before? What did they earn? A sudden drop in income right around separation raises eyebrows.

Education and Qualifications

A lawyer who's suddenly "only able" to work retail has explaining to do. Your qualifications establish your earning potential.

Health and Age

Legitimate health issues can explain unemployment. Age matters too—courts are more understanding of a 60-year-old having trouble finding work than a 35-year-old.

Job Search Efforts

Are they actually looking for work? Applications, interviews, rejection letters, networking—all evidence of genuine effort. No evidence of job searching? That suggests the unemployment is voluntary.

Local Job Market

What jobs are available in their field? What do they pay? Courts look at real market conditions, not hypothetical dream jobs.

Lifestyle vs. Reported Income

If they're living large on supposedly minimal income, something doesn't add up.

How Courts Calculate the Imputed Amount

Courts can't just pick a number out of thin air. The Ontario Court of Appeal has been clear: there must be a "rational basis" for whatever income is imputed.

In practice, courts typically look at:

- Previous earnings — What they made before the suspicious income drop

- Industry standards — What similar jobs pay in the current market

- Minimum wage as a floor — If someone can work but claims they can't find anything, courts often impute at least minimum wage for full-time work

- Expert evidence — Sometimes vocational experts testify about earning potential

Example: The "Rational Basis" Test

Marcus was a project manager earning $85,000. He quit and now works part-time at his brother's company for $25,000.

The court looks at job postings for project managers in his area. Average salary: $78,000-92,000. His previous salary of $85,000 fits that range.

Result: Income imputed at $85,000—there's a rational basis (his actual previous salary in line with market rates).

The Exceptions: When Courts Won't Impute Income

Income imputation isn't automatic just because someone's not working. There are legitimate reasons for unemployment or underemployment:

Childcare Responsibilities

If a parent is the primary caregiver for young children, courts often won't impute income—or will impute a reduced amount that accounts for part-time work only. The age of the children matters: caring for a 2-year-old is different from caring for a 14-year-old.

Health Issues

Genuine health problems that prevent work are valid reasons for unemployment. But you need medical evidence. Vague claims of "stress" without documentation won't cut it.

Reasonable Education or Retraining

If someone is getting education that will improve their earning potential, courts may not impute income during that period—within reason. A 2-year nursing program? Probably reasonable. A 6-year philosophy PhD at age 50? Harder sell.

Involuntary Job Loss

Getting laid off isn't voluntary. But the clock is ticking. Courts expect you to actively look for new work. Six months of unemployment with active job searching? Understandable. Two years with no effort? Income gets imputed.

Market Conditions

If someone genuinely can't find work in their field despite trying, courts consider that. This was more common during COVID—courts recognized that some industries simply shut down.

Imputed Income Works Both Ways

Don't forget: this isn't just a tool for payors to use against recipients. It works in reverse too.

If you're the lower-earning spouse and your ex suddenly "can't afford" support because they quit their $200,000 job to become a yoga instructor, you can ask the court to impute their previous income.

The same rules apply: you need to prove the income reduction was voluntary and unreasonable.

Strategic Considerations

Here's the practical advice part:

If You Think Your Ex Is Hiding Income:

- Document the lifestyle inconsistencies (photos, social media posts, property records)

- Get proper financial disclosure through the legal process

- Consider whether a forensic accountant is worth the cost

- Don't make accusations you can't back up—it hurts your credibility

If You're Worried About Income Being Imputed to You:

- Document your job search (applications, interviews, responses)

- Get medical documentation if health is an issue

- Be realistic about what you can earn—lowballing looks bad if caught

- If you voluntarily reduced your income, have a damn good reason

Try the Calculator

Wondering what support might look like in your situation? Our calculator uses the actual SSAG formulas to give you a realistic range.

Keep in mind: the calculator uses the incomes you enter. If you think income should be imputed differently than what's on paper, you'll need to adjust the numbers to see how that affects the result.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is imputed income in Ontario divorce cases?

Imputed income is when the court assigns an income amount to someone based on what they could earn—not what they actually earn. If your ex quit their job, is working part-time when they could work full-time, or is hiding income through a business, the court can calculate support based on their earning potential instead of their actual paycheque.

Can income be imputed if my ex refuses to work?

Yes. If your ex is voluntarily unemployed—meaning they're capable of working but choose not to—the court can impute income to them. However, there are exceptions: if they're caring for young children, dealing with legitimate health issues, or pursuing reasonable education, the court may not impute income. The key word is "voluntary."

What evidence do I need to prove my ex should have income imputed?

You'll need to show: (1) your ex's employment history and qualifications, (2) evidence they're capable of working, (3) job availability in their field, and (4) that their unemployment or underemployment is voluntary. Tax returns, resumes, job postings, and evidence of job search efforts (or lack thereof) are all relevant.

Can income be imputed to the support payor, not just the recipient?

Absolutely. Income imputation works both ways. If the payor deliberately reduces their income to avoid paying support—like quitting a high-paying job or hiding money through a corporation—the court can calculate support based on what they should be earning. This is actually one of the more common scenarios.

How do courts determine how much income to impute?

Courts look at education, work history, skills, age, health, and local job market conditions. They need a "rational basis" for any number they pick—they can't just guess. Often, they'll look at what the person earned before, what similar jobs pay, or use employment data to determine a reasonable income level.

What if my ex got laid off? Can income still be imputed?

Getting laid off is involuntary, so income won't be imputed immediately. But here's the catch: if they stay unemployed for an unreasonably long time without making real efforts to find work, income can eventually be imputed. The court expects people to actively job search after an involuntary job loss.