The date of separation is the single most important date in your divorce. It locks in property values. It sets the baseline for support. It starts limitation clocks. Get it wrong—or fail to document it—and it can cost you tens of thousands of dollars.

And here's what most people don't realize: you don't both have to agree on it. One spouse deciding the marriage is over is enough.

The Four Key Dates in Ontario Divorce

Date of Separation: When the marriage ends. Sets property values. Most important date.

Date of Marriage: Determines what counts as "premarital" assets you can deduct.

Valuation Date: Same as separation date in most cases. When assets/debts are valued.

Date of Divorce: When you can legally remarry. Usually happens much later.

The Date of Separation: What It Actually Means

Under Ontario's Family Law Act, the date of separation is defined as "the date the spouses separate and there is no reasonable prospect that they will resume cohabitation."

Here's what that means in plain English: it's the date when at least one of you decides the marriage is over—and communicates that decision.

You Don't Both Have to Agree

This catches people off guard. Your spouse doesn't have to accept that the marriage is over for it to be legally over. If you've decided the relationship is finished and you've communicated that, you're separated.

One spouse saying "I want a divorce" (or "this marriage is over" or "I'm done") and meaning it is enough. The other spouse can disagree, hope for reconciliation, refuse to accept it—doesn't matter. The marriage is still over as of that communication.

What Counts as "Communication"?

There's no formal requirement. You don't need to file paperwork. You don't need a lawyer. You can communicate the end of your marriage through:

- A conversation (though this is harder to prove later)

- A text message

- An email

- A letter

- Moving out

- Any clear communication that the marriage is over

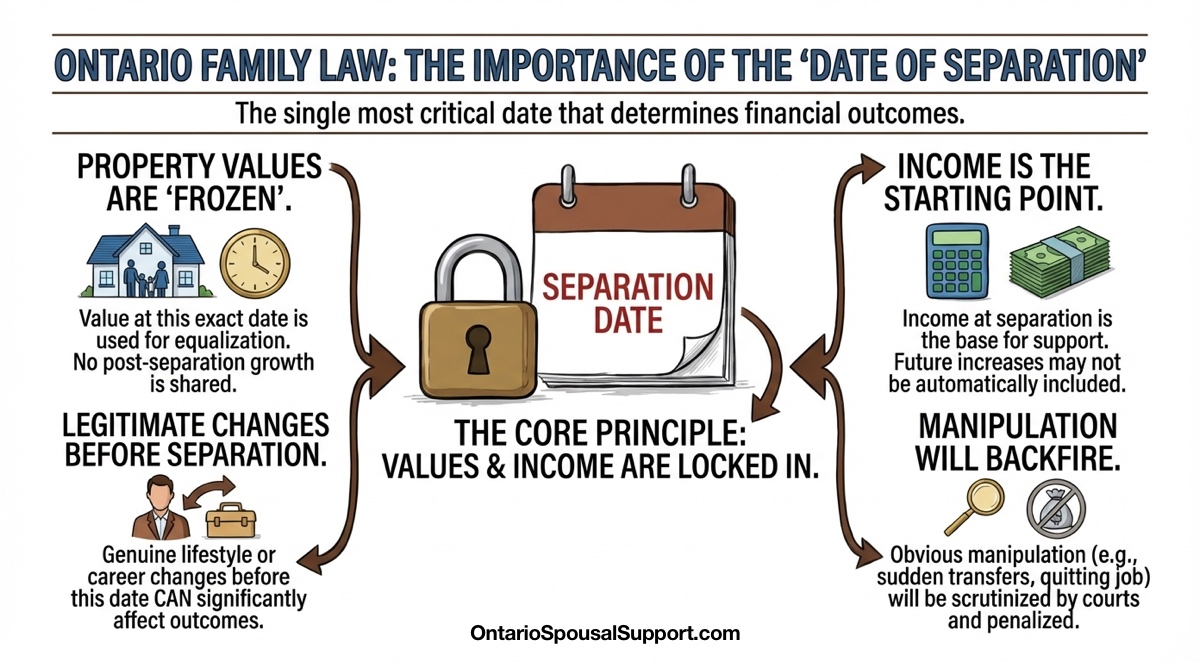

Why the Separation Date Matters So Much

The separation date isn't just administrative. It has real financial consequences.

1. It's the Valuation Date for Property

Under the Family Law Act, the separation date is also the "valuation date" for property division. All your assets and debts are valued as of this date.

This means:

- If your house goes up $50,000 after separation, that increase isn't shared

- If your investments crash after separation, that loss is yours alone

- If you pay down debt after separation, you don't get credit for it in equalization

Example: Why the Date Matters for Property

Mark and Lisa disagree on their separation date. Mark says it was January 2025. Lisa says it was June 2025.

In that 5-month window, their house increased in value by $40,000 and Mark received a $30,000 bonus.

If the separation date is January: that $40,000 house increase and $30,000 bonus don't get equalized—they're Mark's alone.

If the separation date is June: both amounts are included in equalization, and Lisa gets half.

The difference: $35,000 to Lisa, depending on which date the court accepts.

2. It Starts the Divorce Clock

In Canada, you need to be separated for one year before you can get a divorce (unless you're claiming adultery or cruelty, which is rare). The separation date starts that clock.

You can file for divorce before the year is up, but the court won't grant the divorce until you've been separated for 12 months.

3. It Sets Support Calculation Baselines

While support can be recalculated based on current income, the incomes at or around separation often become the starting point for negotiations. Significant income changes right before separation get scrutinized. (See our article on Strategic Moves Before Filing.)

4. It Triggers Limitation Periods

The separation date starts several legal clocks:

- 6 years to bring a property equalization claim after separation

- 2 years after divorce to bring an equalization claim

- Various other limitation periods under family law legislation

Miss these deadlines, and you may lose your rights entirely.

The Date of Marriage: What Counts as Premarital

The date of marriage matters because it determines what assets you can deduct as "premarital."

For equalization, you calculate your net worth at separation, then subtract your net worth at marriage. The difference is your Net Family Property (NFP). Whoever has higher NFP pays half the difference to the other.

So assets you owned at the date of marriage can be deducted—you don't have to share them. But there's a major exception: the matrimonial home. Even if you owned it before marriage, you can't deduct its premarital value.

Married vs. Common-Law: Different Rules

This is important: the property equalization rules only apply to married couples. Common-law partners don't have automatic equalization rights under Ontario's Family Law Act.

For common-law couples, the date you started living together matters for spousal support (if you lived together for 3+ years or have a child), but property division works differently. Each person keeps what's in their name unless you can prove a trust claim.

Separated Under the Same Roof: Yes, It's a Thing

Here's something that surprises people: you can be legally separated while still living in the same house.

It's called "separated under the same roof," and Ontario courts recognize it. You don't have to move out to be separated.

Why People Do This

Plenty of good reasons:

- Can't afford two households (especially in Toronto's housing market)

- Want to minimize disruption for the kids

- Waiting for the house to sell

- One spouse can't afford to move immediately

- It's winter and nobody's finding an apartment

Whatever the reason, the law accommodates it.

What Courts Look For

Living in the same house but claiming to be separated requires proof. Courts look at what's called the "Oswell factors" (from the case Oswell v. Oswell):

- Separate sleeping arrangements: Are you in different bedrooms?

- No sexual relationship: Have you stopped being intimate?

- Separate meals: Are you cooking and eating separately?

- No shared social activities: Have you stopped going to events as a couple?

- Separate finances: Are bank accounts, bills, and expenses separated?

- No household services for each other: Stopped doing each other's laundry, cooking for each other?

- Communication about the relationship: Have you told family and friends you're separated?

You don't need to check every box, but you need to show you've withdrawn from the marriage relationship—that you're living like roommates, not spouses.

When Spouses Disagree on the Date

Disputes about the separation date are common. One spouse wants an earlier date (to exclude certain assets or income), the other wants a later date. Or one spouse genuinely remembers it differently.

How Courts Decide

If you can't agree, a judge will look at the evidence and pick a date. Courts consider:

- When did you stop sleeping in the same bedroom?

- When did you tell family and friends the marriage was over?

- When were finances separated?

- When did one spouse move out (if applicable)?

- When was there a clear communication that the marriage was over?

- What do the contemporaneous records show? (texts, emails, journal entries)

The burden of proof is on the person claiming the earlier date. If you say separation was January and your spouse says June, you need to prove January.

Example: Proving an Earlier Separation Date

Sandra claims separation was March 1. Her husband Paul claims it was July 15.

Sandra's evidence:

- A text message from March 1 saying "I'm done, this marriage is over"

- Testimony from her sister that Sandra told her they'd separated in early March

- Bank records showing she opened a separate account on March 3

- Her mother's affidavit confirming Sandra moved into the spare bedroom in March

Paul's evidence:

- They went to a family wedding together in May

- He hoped they would reconcile

Result: Sandra's evidence is stronger. The court accepts March 1 as the separation date. Paul's hope for reconciliation doesn't override Sandra's clear decision to end the marriage.

Reconciliation: Does It Reset the Clock?

What if you separated, tried to work things out, then separated again?

The Divorce Act has a 90-day rule: you can attempt reconciliation for up to 90 days without resetting the one-year divorce clock. If you get back together for 3 months and then separate again, your original separation date usually stands.

But if the reconciliation is genuine and lasts longer—you actually resume the marriage relationship—then yes, the clock resets when you separate again.

Half-hearted attempts don't count. Going to a couple of counseling sessions while one spouse has already mentally checked out isn't "reconciliation." There needs to be a genuine resumption of the marriage.

The Date of Divorce: Less Important Than You Think

People often focus on "getting divorced" as the goal. But the divorce date is actually the least important of the four key dates.

What the Divorce Date Does

- Allows you to legally remarry

- Officially ends the marriage

What the Divorce Date Doesn't Do

- Doesn't affect property values (that's the separation date)

- Doesn't change support obligations (those are set separately)

- Doesn't affect custody arrangements

In fact, property division and support are usually settled—either by agreement or court order—long before the actual divorce is granted. The divorce itself is often just paperwork at the end.

You can be separated for years, have all financial matters settled, be living completely separate lives, but not technically divorced until you go through the legal process. Plenty of people do this—divorce costs money and if you're not planning to remarry, there's no rush.

Key Dates Summary Table

| Date | What It Determines | How to Establish |

|---|---|---|

| Date of Separation | Property values, divorce clock, limitation periods, support baseline | One spouse decides it's over and communicates that decision |

| Date of Marriage | What counts as premarital assets (deductible from NFP) | Wedding date for married couples; start of cohabitation for common-law |

| Valuation Date | When assets and debts are valued for equalization | Same as separation date in most cases |

| Date of Divorce | When you can legally remarry | Court grants divorce after 1+ year of separation |

How to Document Your Separation Date

Don't leave this to memory and he-said-she-said later. Document it now.

- Put it in writing to your spouse: Send an email or text stating you consider the marriage over as of [specific date]. Keep a copy.

- Tell family and friends: Have witnesses who can confirm when you told them. Written records (texts, emails) are better than just verbal.

- Separate finances: Open your own bank account. Get your own credit card. Start paying expenses separately.

- File taxes as "separated": Once you've been separated for 90 days, you can (and should) change your marital status with CRA.

- Document living arrangements: If separated under the same roof, take photos of separate bedrooms. Keep records of separate groceries and meals.

- Consult a lawyer: A brief consultation creates a dated record of your separation and gets you advice on next steps.

Try the Calculators

Want to see how the separation date affects property division and support? Our calculators use the actual formulas—including how assets at separation are valued.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the date of separation in Ontario?

The date of separation is when the spouses separate with no reasonable prospect of getting back together. It's when at least one spouse decides the marriage is over and communicates that decision. You don't both have to agree on the date—one spouse's decision to end the marriage is enough.

Can we be legally separated while still living in the same house?

Yes. Ontario recognizes "separated under the same roof." You can live in the same house but be legally separated if you've ended the marriage relationship—separate bedrooms, no longer functioning as a couple, separate finances, not doing things together. Courts look at whether you've withdrawn from the marriage, not just whether you share an address.

Why does the date of separation matter so much?

The separation date is the "valuation date" for property division—all assets and debts are valued as of that date. It also starts the one-year clock for divorce, sets the baseline for support calculations, and triggers limitation periods. Getting this date wrong can cost you tens of thousands of dollars.

What happens if my spouse and I disagree on the separation date?

If you can't agree, a court will decide based on evidence. Courts look at: when you stopped sleeping together, when you told family and friends, when finances were separated, when one spouse moved out or stopped acting as a couple. The burden of proof is on the person claiming the earlier date.

Does trying to reconcile reset the separation date?

Not necessarily. The Divorce Act allows up to 90 days of reconciliation attempts without resetting the one-year clock. Half-hearted discussions don't count—there needs to be a genuine resumption of the marriage. If reconciliation fails, your original separation date usually stands.

How do I prove my separation date?

Document it. Send your spouse a text or email clearly stating the marriage is over as of a specific date. Tell family and friends. Open separate bank accounts. File taxes as "separated." Keep records of when you stopped sleeping in the same room, stopped eating together, and stopped acting as a married couple.